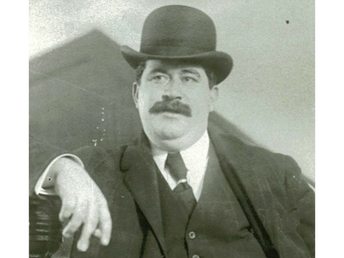

Jerome Bassity, also known as “The King of the Tenderloin,” was the face of vice in San Francisco for almost 15 years. At the top of his power, Bassity, once described as “a man with the moral intelligence scarcely above a trained chimpanzee,” virtually controlled The City’s police force.

Born into poverty in 1876, Bassity was orphaned at the age of 8. To support himself, he sold newspapers by day and ushered in a theatre by nights. Always a hustler, he was making $100 a month by the time he was 11. Bassity’s first adult job, as a milkman, gave no sign of what he would become. He caught the eye of one of his customers, a leading Tenderloin madam who set him up in a saloon at Golden Gate Avenue and Market Street.

Bassity took to the saloon business like an alligator takes to murky water, and he soon branched out into prostitution and gambling. He gained stature by becoming the intermediary between the vice merchants and the corrupt city government, run by Abe Reuf and Eugene Schmitz. By the early 1900s, Bassity was the most powerful underworld figure on the Barbary Coast, owning dozens of brothels.

In 1906, Bassity demonstrated his influence by opening a new brothel, despite the activities of a grand jury that was investigating his activities.

“I don’t give a snap for the grand jury,” he said. “I’m going to open, and they can’t stop me.” And he did, opening a new brothel at 1731 Commercial St. with a wild debauch in which everything was free.

In 1907, Bassity extended his reach into the Tenderloin when he bought the Coronado Saloon on Mason and Ellis streets. Saloonkeepers in the area were delighted because they knew that wherever Bassity went, prostitution and gambling were sure to follow.

Bassity’s rackets brought him around $8,000 a month — $160,000 in 2015 money — and he was a firm believer in the “if you got, it flaunt it” philosophy. He wore three diamond rings on each hand, a huge gem on his shirtfront and more than 50 custom-made, embroidered waistcoats. He spent enormous sums on jewelry, most of which went to prostitutes at his competitor’s brothels. But despite his heavy spending, he was rarely a welcome guest due to his behavior. Bassity was always armed, drank heavily and often ended an evening by shooting out the lights in the brothel. He was arrested twice for shooting at people on the street.

In the early morning of Feb. 8, 1908, a drunken Bassity began yelling and looking for trouble in a restaurant. Trouble, in the form of an angry waiter and cook, found him and responded by beating him to the floor. He was saved by police, who took him to the hospital and then to jail for disturbing the peace.

The reform movement temporarily closed Bassity’s businesses, but he was able to reopen everything in 1910, when Patrick McCarthy was elected mayor. As the manager of McCarthy’s non-political Liberty League, Bassity raised huge sums for McCarthy’s campaign.

McCarthy promised to “make San Francisco the Paris of the West,” and Bassity was just the man to put the sin back in San Francisco. Bassity became part of a triumvirate who controlled the police force.

First, Bassity got his friend, Dan White, appointed as police chief. Then, he brought all the corrupt police back to the Tenderloin and sent honest policemen, like Arthur Layne (great grandfather of Governor Jerry Brown), to the outlying districts. Gambling and prostitution flourished, and “Bunko Men” trolled the Ferry Building to lure the unwary to Bassity-owned clubs.

When “Sunny Jim” Rolfe was elected mayor in 1912, Bassity’s power began to fade. The years of high living were showing as his double chin began to multiply and his pants expanded annually. But though his body enlarged, his common sense remained tiny.

Bassity started a bar fight with an Alaskan fisherman, who pounded him like a fat piece of abalone. Bassity threatened reprisals but didn’t follow through and lost his stature in the underworld. By 1917, Bassity’s influence was gone and he was arrested for serving a soldier in his saloon.

How far the mighty had fallen.

The rest of Bassity’s life was anti-climactic. He sold his interests in San Francisco, moved to Southern California and spent most of his resources in a failed attempt to buy a Tijuana racetrack. When he died in San Diego in 1929, he left an estate of less than $10,000.

Born into poverty in 1876, Bassity was orphaned at the age of 8. To support himself, he sold newspapers by day and ushered in a theatre by nights. Always a hustler, he was making $100 a month by the time he was 11. Bassity’s first adult job, as a milkman, gave no sign of what he would become. He caught the eye of one of his customers, a leading Tenderloin madam who set him up in a saloon at Golden Gate Avenue and Market Street.

Bassity took to the saloon business like an alligator takes to murky water, and he soon branched out into prostitution and gambling. He gained stature by becoming the intermediary between the vice merchants and the corrupt city government, run by Abe Reuf and Eugene Schmitz. By the early 1900s, Bassity was the most powerful underworld figure on the Barbary Coast, owning dozens of brothels.

In 1906, Bassity demonstrated his influence by opening a new brothel, despite the activities of a grand jury that was investigating his activities.

“I don’t give a snap for the grand jury,” he said. “I’m going to open, and they can’t stop me.” And he did, opening a new brothel at 1731 Commercial St. with a wild debauch in which everything was free.

In 1907, Bassity extended his reach into the Tenderloin when he bought the Coronado Saloon on Mason and Ellis streets. Saloonkeepers in the area were delighted because they knew that wherever Bassity went, prostitution and gambling were sure to follow.

Bassity’s rackets brought him around $8,000 a month — $160,000 in 2015 money — and he was a firm believer in the “if you got, it flaunt it” philosophy. He wore three diamond rings on each hand, a huge gem on his shirtfront and more than 50 custom-made, embroidered waistcoats. He spent enormous sums on jewelry, most of which went to prostitutes at his competitor’s brothels. But despite his heavy spending, he was rarely a welcome guest due to his behavior. Bassity was always armed, drank heavily and often ended an evening by shooting out the lights in the brothel. He was arrested twice for shooting at people on the street.

In the early morning of Feb. 8, 1908, a drunken Bassity began yelling and looking for trouble in a restaurant. Trouble, in the form of an angry waiter and cook, found him and responded by beating him to the floor. He was saved by police, who took him to the hospital and then to jail for disturbing the peace.

The reform movement temporarily closed Bassity’s businesses, but he was able to reopen everything in 1910, when Patrick McCarthy was elected mayor. As the manager of McCarthy’s non-political Liberty League, Bassity raised huge sums for McCarthy’s campaign.

McCarthy promised to “make San Francisco the Paris of the West,” and Bassity was just the man to put the sin back in San Francisco. Bassity became part of a triumvirate who controlled the police force.

First, Bassity got his friend, Dan White, appointed as police chief. Then, he brought all the corrupt police back to the Tenderloin and sent honest policemen, like Arthur Layne (great grandfather of Governor Jerry Brown), to the outlying districts. Gambling and prostitution flourished, and “Bunko Men” trolled the Ferry Building to lure the unwary to Bassity-owned clubs.

When “Sunny Jim” Rolfe was elected mayor in 1912, Bassity’s power began to fade. The years of high living were showing as his double chin began to multiply and his pants expanded annually. But though his body enlarged, his common sense remained tiny.

Bassity started a bar fight with an Alaskan fisherman, who pounded him like a fat piece of abalone. Bassity threatened reprisals but didn’t follow through and lost his stature in the underworld. By 1917, Bassity’s influence was gone and he was arrested for serving a soldier in his saloon.

How far the mighty had fallen.

The rest of Bassity’s life was anti-climactic. He sold his interests in San Francisco, moved to Southern California and spent most of his resources in a failed attempt to buy a Tijuana racetrack. When he died in San Diego in 1929, he left an estate of less than $10,000.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed